Fostering Community Resilience Through Youth Mentorship: Q&A with Jessica Greenawalt of The Arthur Project

Take a moment to imagine your middle school self. What comes to mind first? Perhaps you think back on what it was like to adjust to a new school and academic pressures. Or you remember navigating difficult social situations with your friends, or the less than stylish haircut you had when you were 12. For many adults, middle school years are not a time looked back on fondly.

Now, imagine being a middle schooler in today’s world. An already isolating time of physical, mental and emotional growth is amplified by a global pandemic that’s keeping young students at home, away from their friends, teachers and support networks. Many young people are wondering about their place and future in a country that’s experiencing a national reckoning on racial, social and economic justice. Young people of color who live in marginalized communities are disproportionately affected by these challenges and uncertainty.

Jessica Greenawalt sees the impact these stressors have on youth and their families in her work every day. She is the new Executive Director of The Arthur Project, a New York City-based organization that provides youth mentoring and other resources for underserved middle school students and their families, and a grantee of The Pascale Sykes Foundation. We had the chance to connect with Jessica about The Arthur Project’s unique youth mentoring program, what these programs look like during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how adapting the Whole Family Approach has strengthened their services.

1. What kinds of services does The Arthur Project provide for youth in The Bronx?

The Arthur Project provides therapeutic mentoring services to middle school students and their families to support a number of outcomes later in life. Our Whole Family Approach sets the foundation for our work with students, families and service providers, ensuring we all work together. While we try to make room for anyone to join our program, we use chronic absenteeism as a flexible parameter for determining eligibility in our program, meaning we invite students to join who may be experiencing challenges with attendance. Most students join at the beginning of sixth grade and stay through their eighth-grade graduation.

When a student first enters our program, they and their parent or guardian meet with a Family Advocate to set collaborative goals related to school performance, such as improving attendance or grades, or developing a better relationship with a teacher. They can also choose to set additional family goals in five categories: (1) School and Career; (2) Finance; (3) Family, Friends and Relationships; (4) Community and Culture; and (5) Health and Wellness.

Next, students are matched with a therapeutic mentor with whom they meet one-on-one for one to two hours each week during the school year. Mentors are graduate social work students who are clinicians-in-training. They work with students to set and achieve individual goals, and discuss anything from family, friends and school to identity, trauma, or anything else going on in that student’s life. Students and mentors also participate in extracurricular and community-based activities together, ranging from art therapy, to improv, and cultural events. These activities are curated to help students work toward =goals and develop essential life skills.

2. Why does your service model focus on middle school-aged kids?

Emerging research in adolescent development indicates that a number of academic, neurological and social-emotional milestones converge during the middle school years, forming a unique and critical juncture in the lives of youth. A strong performance in middle school — marked by regular attendance, satisfactory grades, and positive engagement with teachers and peers — is correlated with a high level of academic engagement in high school, which has a significant impact on their life trajectory.

In other words, the adolescent brain is still “under construction,” which means youth interventions during middle school are likely to have a powerful and lasting impact. Despite this uniquely important time in a child’s life, middle school educational programming remains one of the least well-funded areas in youth development. The Arthur Project is designed to provide a strong base of support to youth during this often-overlooked inflection point.

3. What are the most significant ways the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted The Arthur Project’s ability to provide services?

This has been a time of great uncertainty for the students and families we serve, and we’re hearing that our services are more important than ever. While we are still learning about best practices for meaningful remote engagement, generous support from the Pascale Sykes Foundation allowed us to quickly pivot from in-person services to online individual and group engagement. For the most part, this has taken the form of video sessions via Zoom or Google. In some instances, mentors and mentees hold sessions over the phone.

This process has been successful largely thanks to the established trust between mentors and mentees. The way students and their families are accessing services may have shifted dramatically, but the foundation of trust they have built with their mentor is more important now than ever. Looking ahead, we will spend time reflecting on the value of remote services and consider how we might permanently integrate them into our service model to improve the flexibility of our services and engage families in ways that may work better for them.

4. What have you found are the greatest challenges facing young people and their families at a time when our country is experiencing a national reckoning on racial, social and economic justice, and communities across the country continue to face immense hardship in the wake of COVID-19?

As an organization situated in The Bronx serving primarily Black and Latinx families, we recognize that the issues that are now at the center of the mainstream national conversation have long been the experiences of many of the children and families we serve. Issues such as racial abuse, brutalization at the hands of the police and mass incarceration of Black men and women, as well as systemic inequities like discrimination in employment, education and housing, disproportionately impact our students and their families. They are surviving and thriving in a society that was designed to oppress them.

Racial disparities in COVID-specific health care and mortality rates are further examples of our society’s ongoing inability to care for and value Black and Latinx lives. The vast majority of the challenges our students and families face are not characterological, pathological or psychiatric; they are a direct result of centuries of racial and economic inequity. Our program is designed to create space for families to process and heal from the traumas that are still being inflicted while creating opportunities to build access to important opportunities and relationships.

6. The relationship between adults and children is instrumental within the Whole Family Approach. Why is relationship building such an integral part of your approach?

We believe that positive relationships are a vehicle for growth and change. Through a trusting mentor-mentee relationship, students are given the space to tap into their strengths and capabilities, safely process the traumas that have been inflicted upon them, and develop an expanding sense of self and the impact they can make in the world.

To drill down further, mentors work with students to help them internalize a sense of “mattering,” which affects how they view themselves and whether they believe they have an impact on the world around them. By reinforcing to students that they matter, students are in turn more likely to take positive actions like supporting their families and taking action in their communities.

7. What prompted The Arthur Project to want to incorporate the Whole Family Approach into your work helping middle schoolers?

We have always understood that meaningfully supporting our students meant building connections with and supporting their caregivers as well. At first, we were delighted to see important relationships between mentors and caregivers develop organically. However, we had no structure in place to strengthen The Arthur Project’s relationships with families, nor the tools to support the caregivers of the children we worked with. It seemed serendipitous when we had the pleasure of meeting Fran and Jackie from the Pascale Sykes Foundation during our second year. We partnered to launch a pilot program to provide Whole Family Approach therapeutic mentoring services shortly thereafter.

We recently completed our first year of Whole Family Approach programming for a small subset of families. As a result of many lessons learned and ongoing support from the Foundation, we are excited to expand our implementation of the Whole Family Approach to offer services to all families whose students are enrolled in our mentoring program.

8. How is The Arthur Project adjusting its services as much of the country remains closed and schools strategize about the potential of reopening in the fall?

Thanks to generous and responsive support from the Pascale Sykes Foundation, we were able to offer our mentors the opportunity to continue under paid contracts through the end of summer, even though our programs typically break for the summer in June. In addition to the individual and group services from our mentors, our Family Advocates are facilitating a virtual Whole Family Approach summer workshop series intended to help our outgoing 8th graders and their families prepare for high school and beyond. Through the summer program, students and families will receive support in developing technology skills, organizational and study skills, along with skills related to financial literacy and independence.

9. The Arthur Project emphasizes the importance of community service as a core component of each child’s development. What impact has the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing racial justice movement had on this part of the program?

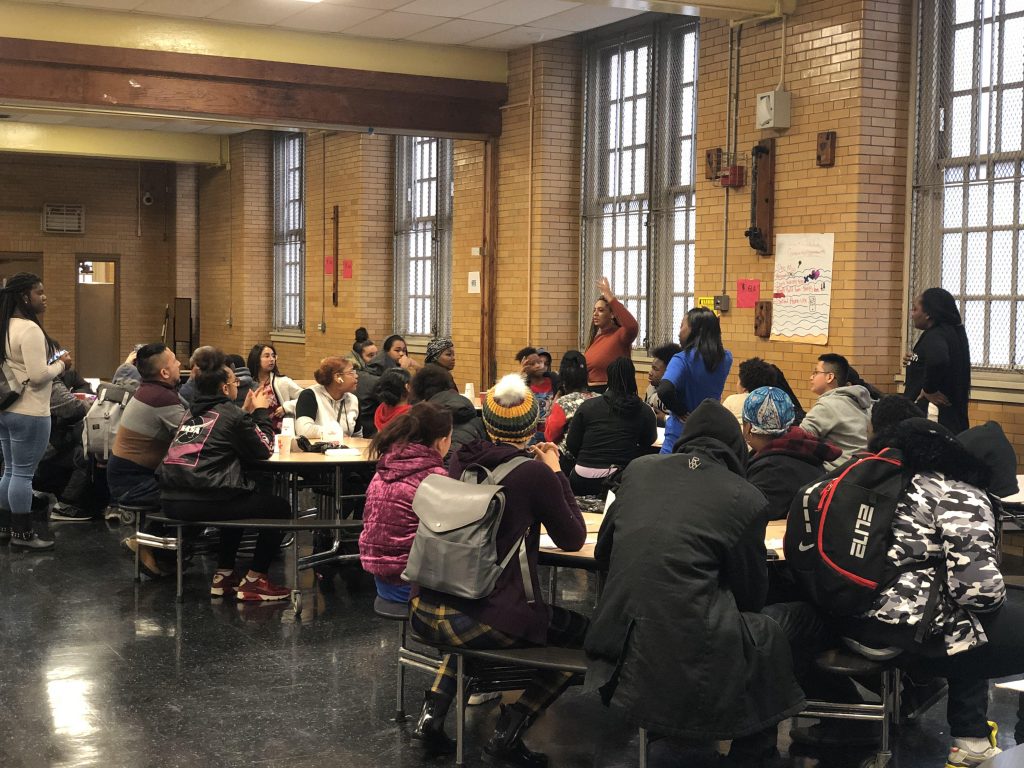

In the last three years, we have learned a great deal about meaningful, appropriate social justice issues for our students to tackle. In response, instead of one-off volunteer engagement opportunities, we have re-orientated the service component of our program to focus on the development of students’ long-term organizational and leadership skills. For example, we formed a Student Leadership Council of 8th grade students who act as an advisory council to our organization. This group facilitates The Arthur Project Town Hall events, where they present and analyze current issues that are important to them. Students learn to assess needs in their community and how to communicate those needs to appropriate audiences. For example, one Town Hall series focused on understanding and promoting the U.S. Census, as The Bronx is a historically undercounted — and thus under resourced — community.

We also create space for students to process difficult topics in the news individually and in groups. Police brutality, for example, is an issue too close to home for many of our students and their caregivers, and in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, many sought an outlet to process their feelings. In one of our student activity groups, MadRaps, students participate in facilitated discussions on issues like police brutality, and how they connect to greater systemic forces of oppression. Group participants then write out their thoughts, pair them with a rhythm and beats, and perform them in an end-of-year showcase.

10. Looking ahead, what’s on the horizon for The Arthur Project? Do you have any new programs or research in the works?

As we wrap up our third year of operation, we are taking time to reflect on the successes and challenges we’ve faced, with a particular eye toward identifying what has really worked for our students and families. We are also beginning to harness and contribute to research around the particular nuances of a healthy, happy and impactful adult-child relationship. Our hope is that in the years to come, we will be able to provide a model of service for others doing similar work who are interested in the positive impact of intergenerational relationships.